Controversy: 1878-1889

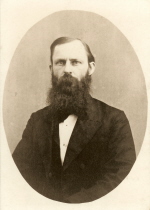

Southern encountered its first major controversy in 1879, when professor Crawford Howell Toy came under fire for his views. Toy was brilliant. He completed the seminary course in one year and pursued advanced studies in Berlin for additional years. He became Southern’s fifth professor in 1869. Toy initially professed firm belief in biblical truth, declaring in his inaugural address that without the Bible, man is “on a boundless ocean, wrapped in darkness.” (1) But Toy embraced Darwinian evolution and naturalistic “higher criticism” of the Old Testament. He became convinced that Scripture contained error, science trumped Scripture’s plain meaning, and conscience was the test of truth. The orthodoxy Toy claimed stood in stark contrast to the false interpretations he believed.

In the late 1870s, Toy’s fellow professors labored to persuade him of his errors. By 1879, his position was no longer tenable and he resigned. Standing with Toy just before his departure, his friend Boyce exclaimed that he would give his right arm for Toy to return to orthodoxy. Toy never returned. Afterward, he joined the faculty of Harvard University, where he founded the Semitic Languages department and attended a Unitarian church. The rise of his academic star contrasted with the fall of his theology. The man once engaged to missionary Lottie Moon authored criticism of the Bible so radical that it offended many Unitarians.

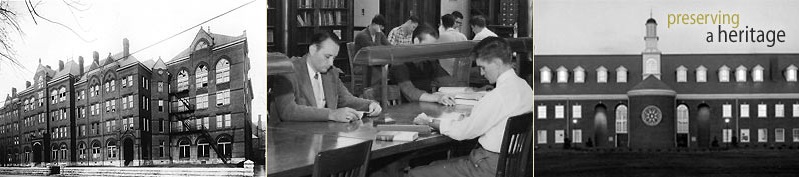

The seminary community faced other challenges. The faculty carried out constant fundraising efforts in the 1880s and traveled extensively to solicit donations. Notable successes included fifty thousand dollars from U.S. Senator Joseph E. Brown of Georgia and twenty five thousand dollars from prominent Baptist oilman J. D. Rockefeller. On the strength of these gifts, the seminary constructed its first major building, New York Hall, in 1888 in downtown Louisville. The building housed 200 people and had room for classes, dining, and personal study.

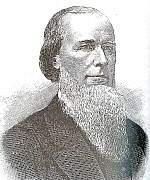

The sustenance of Southern involved continual sacrifice for the founding four. Boyce above all exhausted himself for the seminary. Having served as chairman of the faculty from Southern’s founding, the trustees elected him president in 1888. In his role, he would “for weeks in succession, begin work at five a.m., and continue, with variety, but no intermission, till eleven p.m.” (2) This schedule not only sparked the seminary to life, it spent Boyce’s own. In 1889, on vacation in Europe to restore his health, Boyce passed away.

His close friend Broadus memorialized Boyce in his Memoir of James P. Boyce: “O brother beloved, true yoke-fellow through years of toil, best and dearest friend, sweet shall be thy memory till we meet again! And may the men be always ready, as the years come and go, to carry on, with widening reach and heightened power, the work we sought to do, and did begin!” These express well the love and commitment the first faculty shared. By their perseverance, Southern came to life. This is the legacy of the founding four.

(1) Mueller, A History of Southern, 137.

(2) Broadus, Memoir of James P. Boyce, 367.