Ambition: 1919-1928

In the years following World War I, an ambitious vision hastened the seminary’s advance. When the Southern Baptists launched their great fundraising effort, the “75 Million Campaign,” in 1919, Mullins announced his own campaign to raise an additional two million dollars for the seminary. While the 75 Million Campaign ultimately failed to reach its goals, Southern obtained sufficient funds from it and from its own campaign to begin several building projects, each accomplished through Mullins’s enterprising spirit.

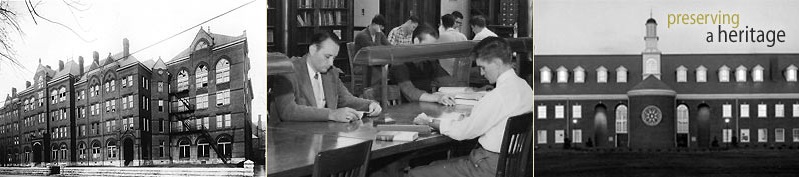

Mullins intended above all else to relocate Southern’s campus to a thirty-four-acre estate on Lexington Road, six miles away from the Seminary’s downtown location. “The Beeches,” as it was called, did not come cheaply, however. By the time the Seminary moved from its downtown spot, the cost of the building plan had ballooned to nearly three and a half million dollars. Though some questioned the wisdom of Mullins’ push in light of the financial risk it represented, the growth of the student body, at a high of 442 in 1923-1924, necessitated action.

The seminary began a new course of study in this era, calling on Gaines Dobbins to begin teaching on church efficiency, a forerunner to the church growth movement, and Sunday school pedagogy. Southern also kept pace with the growing interest in sociology, enlisting W. O. Carver and C. S. Gardner to develop the subject’s curriculum.

In the 1920s, as evolution spread to the public schools and liberalism spread in the denominations, Southern Baptists responded by forming a seven-person committee to draft a confessional statement for the Convention, called the Statement of Baptist Faith and Message. Mullins, President of the SBC from 1922 to 1924, chaired the committee. Under his leadership, the group produced a statement that expressed Southern Baptists’ commitment to traditional Baptist orthodoxy, including God’s special creation of humanity and scriptural miracles. Mullins sought to integrate objective Bible truth with subjective Christian experience. Some Baptist leaders took Mullins’s emphasis on experience to establish a shift toward conscience as the arbiter of truth. Years later, the shift would balloon to alarming proportions.

In late November 1928, the convention leader and seminary president suffered a stroke. After several days in bed, Mullins passed away on Friday, November 23rd, leaving his city and school in mourning.